27 Apr A Loss of Control that Leads to a Conversion

The Acts of the Apostles contains three stories (chap. 9, 22, 26) on the conversion of Saul, also known as Paul, initially a ferocious persecutor of Christians, who was not only present but also approved of the stoning of Stephen (Acts 7:58). His conversion, to Christ and to the Gospel, was decisive for the spreading of the Good News in the Mediterranean countries. Moreover, Paul could be the most prolific author of the New Testament.

As concerns his conversion, it was the result of a destabilizing epiphany while Paul was traveling to Damascus, the bearer of letters from the high priest of Jerusalem addressed to the synagogues of the city, “having at last been authorized to lead men and women he’d found—followers of Christ’s teachings—to Jerusalem in chains.” In short, it was an operation of the religious police, with whom he was familiar, having already brought many Christians to jail (Acts 22:4). On the road, he was suddenly enveloped by a blinding light that caused him to fall to the ground (Acts 9: 3-4; 22: 6-7; 26:13). A voice commanded him to rise and allow himself to be brought to Damascus by hand – having temporarily become blind – to meet a certain Ananias, who baptized him.

What was his means of transport between Jerusalem and Damascus, two cities located about 300km apart? None of the three stories in the Acts specifies whether he went by foot, donkey, cart, horse, or a caravan of camels. Many historians consider it improbable that he traveled by horse, given that it was considered a sign of compliance with the Roman occupation in that era. It’s true that Paul was a Roman citizen, but it was his unbending adherence to Judaism that he loved to demonstrate and not his status as “collaborator”.

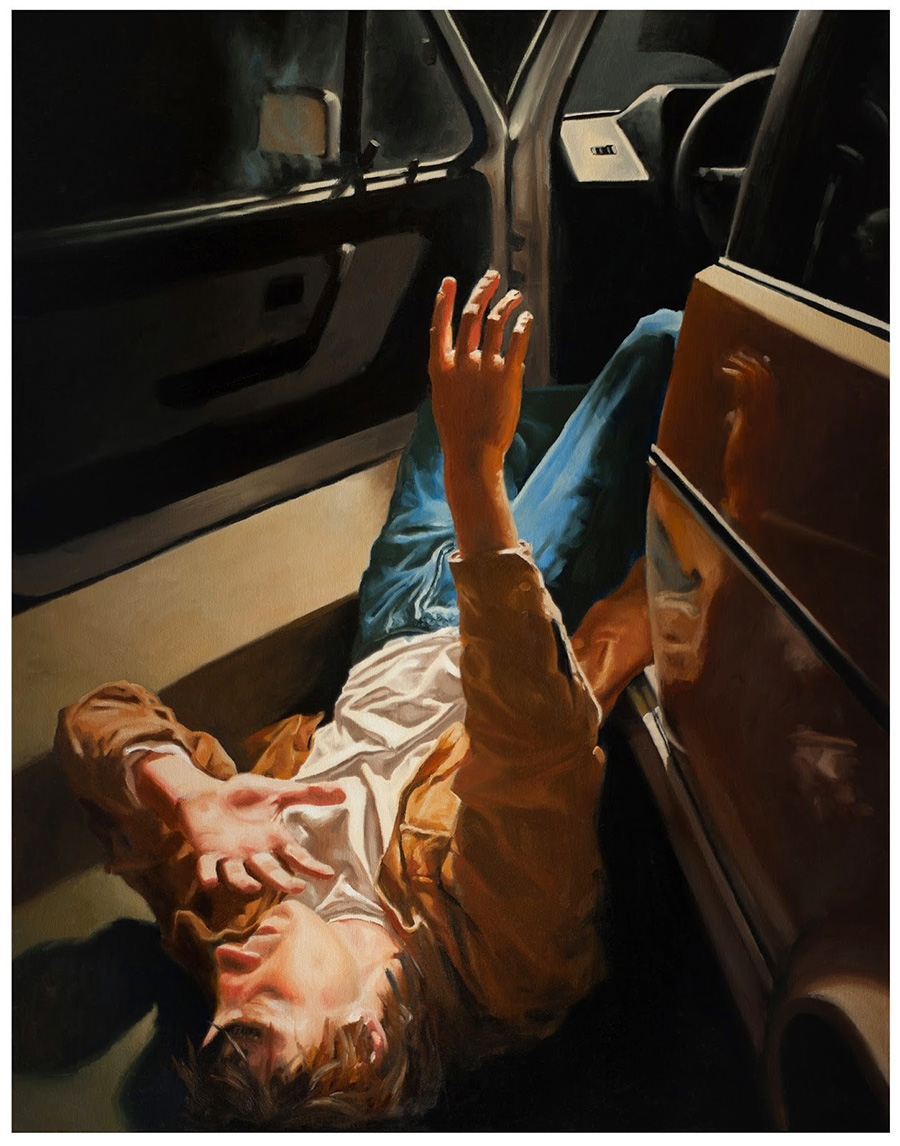

In terms of artists, once the subject of the conversion of Paul became a so-called archetype, they began to depict him as he walked on foot among his companions and, at the moment when he was struck by light, lying supine on the ground. This type of depiction was used for at least three centuries, from the 9th-11th centuries. Still, the very idea of conversion quite early became—from the 12th century on—synonymous with destabilization, and Paul began to be painted thrown from his saddle, dejected, rejected, and above all fallen from his horse. This version was historically improbable but became almost the rule in painting and sculpture…up until our time. Recently, some artists have decided to liberate themselves from this version, also because horses have not been the principle means of transport for the majority of men for quite some time, but rather the automobile.

Thus is the destabilization experienced by St. Paul expressed, albeit in a modern way, by an artist from Kansas, Ernest Vincent Wood III, in his painting pointedly entitled The Conversion of St. Paul. This artist had the idea of abandoning the horse, substituting it with an automobile and transferring the fall from a horse to a loss of control with the steering wheel. From a sociological and anthropological point of view, and above all from a religious point of view, this is both a highly original and also significant choice. The grand emotional shocks, the esthetic turmoil, the religious conversions are in fact manifested with a sudden loss of reference points, at least temporarily. To create a credible idea of what St. Paul saw, the majority of us probably never having experienced falling from a horse, we should instead imagine a loss of control and equilibrium. In any event, that is what this painting suggests, in both a bold and ingenious way.

As concerns his conversion, it was the result of a destabilizing epiphany while Paul was traveling to Damascus, the bearer of letters from the high priest of Jerusalem addressed to the synagogues of the city, “having at last been authorized to lead men and women he’d found—followers of Christ’s teachings—to Jerusalem in chains.” In short, it was an operation of the religious police, with whom he was familiar, having already brought many Christians to jail (Acts 22:4). On the road, he was suddenly enveloped by a blinding light that caused him to fall to the ground (Acts 9: 3-4; 22: 6-7; 26:13). A voice commanded him to rise and allow himself to be brought to Damascus by hand – having temporarily become blind – to meet a certain Ananias, who baptized him.

What was his means of transport between Jerusalem and Damascus, two cities located about 300km apart? None of the three stories in the Acts specifies whether he went by foot, donkey, cart, horse, or a caravan of camels. Many historians consider it improbable that he traveled by horse, given that it was considered a sign of compliance with the Roman occupation in that era. It’s true that Paul was a Roman citizen, but it was his unbending adherence to Judaism that he loved to demonstrate and not his status as “collaborator”.

In terms of artists, once the subject of the conversion of Paul became a so-called archetype, they began to depict him as he walked on foot among his companions and, at the moment when he was struck by light, lying supine on the ground. This type of depiction was used for at least three centuries, from the 9th-11th centuries. Still, the very idea of conversion quite early became—from the 12th century on—synonymous with destabilization, and Paul began to be painted thrown from his saddle, dejected, rejected, and above all fallen from his horse. This version was historically improbable but became almost the rule in painting and sculpture…up until our time. Recently, some artists have decided to liberate themselves from this version, also because horses have not been the principle means of transport for the majority of men for quite some time, but rather the automobile.

Thus is the destabilization experienced by St. Paul expressed, albeit in a modern way, by an artist from Kansas, Ernest Vincent Wood III, in his painting pointedly entitled The Conversion of St. Paul. This artist had the idea of abandoning the horse, substituting it with an automobile and transferring the fall from a horse to a loss of control with the steering wheel. From a sociological and anthropological point of view, and above all from a religious point of view, this is both a highly original and also significant choice. The grand emotional shocks, the esthetic turmoil, the religious conversions are in fact manifested with a sudden loss of reference points, at least temporarily. To create a credible idea of what St. Paul saw, the majority of us probably never having experienced falling from a horse, we should instead imagine a loss of control and equilibrium. In any event, that is what this painting suggests, in both a bold and ingenious way.