23 Oct The Sistine of Bologne: the Oratory of Saint Cecilia

The presence of the porticos in Bologna often makes it difficult to distinguish the religious buildings from each other. In particular, the Oratory of Saint Cecilia would be impossible to find today had a cultural association not undertaken its promotion and development for years.

The reasoning for such discretion can be explained by its original purpose. The single-nave building was once a parish church, set at the back of apse of San Giacomo Maggiore, the grand Augustinian establishment of the 13th century and Palatine church during the reign of the Bentivolgio family, whose home was located where the Teatro Comunale now stands. Some members of the family were interred in the church of San Giacomo and, in particular, one of the chapels of the Gothic tornacoro was rebuilt by the Bentivoglio and completed in the year 1486 as the site of celebration for their family line.

Directly to the right of this chapel is the Oratory of Saint Cecilia, which is only accessible via San Donato Street (today Via Zamboni) which skirts the side of the principle church. Like the Bentivoglio chapel, this too was reconstructed by the powerful family on a pre-existing foundation, due to which it maintained its original dedication.

The architectural renovations of the structure were finished in 1483, but decoration of the walls only began in 1505, completed with a restoration which became necessary following earthquakes which struck the city in the months prior. The frescos were commissioned to court painters, paladins of the sort from the last quarter of the 15th century: Francesco Raibolini known as Francia, Lorenzo Costa, and Amico Aspertini, who was the youngest and most cutting-edge of them all. Amico himself had recently returned from Rome when he became involved in the undertaking. It is unknown who designed the iconography, divided into 10 scenes and taken from the Passio of the saint, which also includes the episodes of the conversion and martyrdom of husband Valeriano and brother-in-law Tiburzio. It is a known fact that in the overall scheme, the decoration of the oratory emulates that of a chapel already much more famous at that time, one desired by Pope Sixtus IV in the Apostolic Palace of the Vatican, its walls decorated by 1483 by the principle Florentine painters of the moment and their students: Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Pinturicchio, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli, Cosimo Rosselli, Piero di Cosimo, Bartolmeo della Gatta. Even before the involvement of Michelangelo Buonarroti, the Sistine Chapel was thus already a model for prestige and modernity. It likely would have also appeared as such to the eyes of Aspertini, who probably played a role in planning the arrangement of the frescos in Saint Cecilia. In both cases, the équipes of artists were active simultaneously and conform to the same narrative criteria–dimensions of the figures, relationship to the landscape, choice of color scale–to lend unity to the narration of the cycles. Although the Bolognese decoration may not have been entirely completed at the top due to the expulsion of the Bentivoglio family from Bologna at the behest of Pope Julius II, and some parts of the frescos were also damaged by modifications to the oratory carried out throughout the centuries, it is a clear redivision which reaffirms the Roman.

There is a false stone frame which outlines the scenes, separated by pilasters decorated with candelabra of exquisite Renaissance taste. The stories are surmounted by a high cornice, the center of which proclaiming the subjects of the scenes written in capital letters. Though the words occupy a single row in the Sistine Chapel, they are divided across two in the Bolognese oratory, probably because the narrated episodes were less familiar to worshippers and had to be described in greater detail so that the images could be understood. Set up above, the windows in both locations are essential for appropriate illumination of the scenes portrayed.

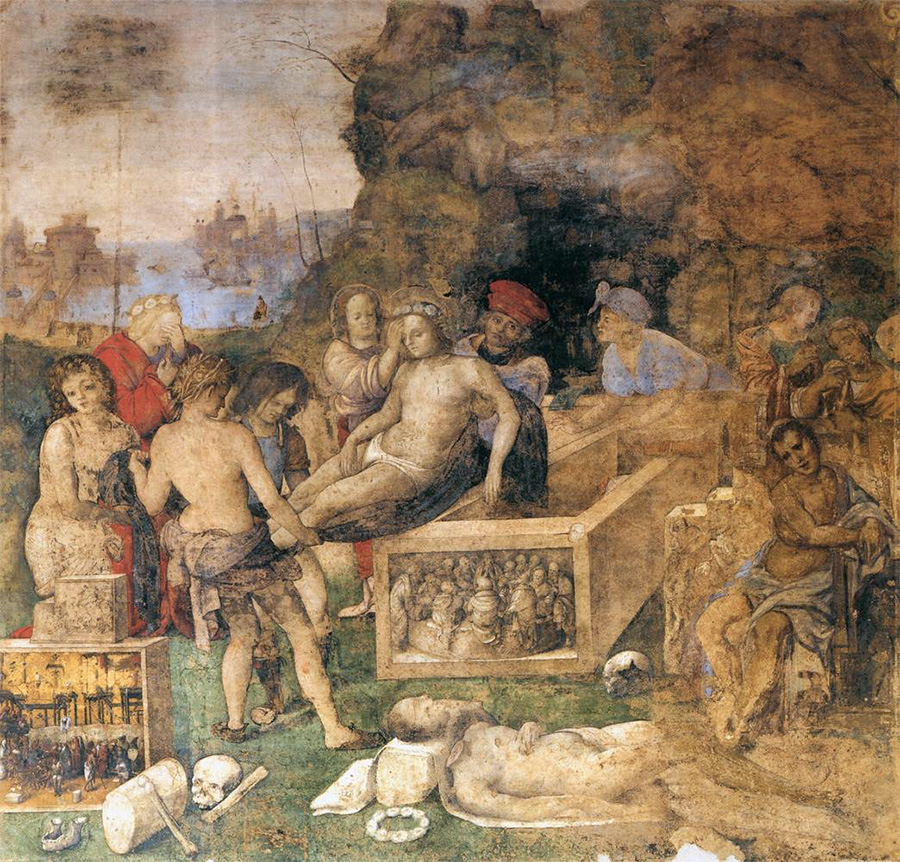

This comparison with the Roman setting was pushed further by Aspertini, who embellished the frescos attributable to him with numerous unusual references to sculptures and ancient monuments seen in Rome, such as the Colosseum or Castel Sant’Angelo. As well as using a rather complicated compositional structure, he unified related episodes occurring at various times by depicting them in the background of the principal scene and represented salient aspects of the story by inserting as decoration sacred objects such as altars and sarcophagi. In so doing, the artist underscored the cult meaning of these episodes, transforming them into parts of monuments of an authoritative past.

In particular, in the scene of the Burial of Saints Valeriano and Tiburzio, the front sides of the stone structures function as modern displays: in the bottom left on an ample parallelepiped, the martyrdom of Saint Cecilia is portrayed in Pompeiian style and, on the smaller panel placed above – in order to imitate a bas-relief – the capture of the saint (today barely visible). In this manner, the diachrony of the narrated story is constantly reaffirmed, thanks to the fact that each episode recalls continually those preceding and those following, such that each scene offers a different point of view on the entirety of the life of the saint, portrayed here as the principal story while the deceased husband and brother-in-law weep. The third display is the front of Valeriano’s sarcophagus, on which a bas-relief of the Last Supper is depicted to underline the value of the sacrifice of the saint, comparing it to that of Christ. Some of the figures shown in the scene are taken from ancient monuments so as to render more convincing the setting of the 3rd century. Among these is the lifeless body of Tiburzio, stretched out next to his severed head, the cadaver’s whiteness causing him to resemble even more the statue of the Niobid from the Maffei collection of Rome, upon which it is based: the eternal memory of the martyr is evoked by the exemplary duration of the ancient marble.

The current conservation state of the Bolognese frescos, which have almost lost the dry finishes in tempera and the gilded details, does not allow the original formal richness to be admired in full. Incompleteness and the damnatio memoriae of viewers contributed to an undervaluation of this early Renaissance masterpiece of northern Italy, created by leading painters involved an important artistic scene, contemporaries not only with Tuscany, but also those of Veneto and Lombardy while still able to give life to an original and poetic language.

Other works of painters active in the Oratory of Saint Cecilia can be admired in the Pinacoteca Nazionale and at the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte in Bologna, as well as in numerous churches in the city.